Session Three - How to get the most out of the New Testament

Introduction

"When the set time had fully come, God sent his Son" (Gal. 4:4a).

The world of the New Testament was a varied and confusing mass of power struggles, philosophies, political parties, religious groups, and ethnicities. There were many gods in the Greco-Roman world; but, as always, people were waiting for a truth that rose above all of that—which is exactly what they found in the Gospel of Jesus.

Jesus is the center of the Bible's message. The Old Testament points forward to him, and the whole of the New Testament is focused on him.

Once we understand who Jesus is and why he came into the world, the rest of the Bible begins to make sense. Hebrews 1:2 reads: "In these last days God has spoken to us by his Son.", cf Luke 24:25-27; John 5:39.

From Events to Records

The New Testament contains twenty-seven books that are divided into five subcategories:

- four gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John)

- the book of Christian history (Acts)

- thirteen Pauline epistles (Romans through Philemon)

- eight general epistles (Hebrews through Jude)

- one apocalyptical epistle (Revelation).

Different people set out their experiences and convictions concerning the meaning and significance of the earthly life of Jesus of Nazareth. None of these writings appeared until some years after Jesus' death and resurrection. He left no written records concerning himself, and any information about him must be gleaned from what other people have written.

By the end of the first century of the Christian era, several biographies of Jesus had been written, four of which (the Gospels, from Old English "god spel", or "good news"; "evangel" in Latin) are now part of the New Testament.

Before any of these biographies was written, Christian communities — later known as churches — had been established, and letters written instructing the members about the Christian way of life and telling them how to deal with local problems.

As the number of Christians increased and their influence was felt in various parts of the then-known world, opposition to the movement arose from different quarters. Jews deeply resented the fact that many of their own people were forsaking Judaism and becoming Christians (mixing with a growing proportion of Gentile converts in the Christian community), but the most severe opposition came from the Roman government, which tried in various ways to suppress, if not to annihilate, the whole Christian movement on the grounds that it constituted a threat to the empire.

When persecution of Christians became extreme, further messages were sent to them by church leaders. These messages, usually in the form of letters or public addresses, which were copied and circulated, encouraged the sufferers and advised them concerning the ways in which they should respond to the demands that were being made upon them. Some of these letters are now part of the New Testament.

Other letters ("epistles", from Greek epistole, or "send news"), several of which have been preserved, were written to counteract false doctrines that arose within the churches. However, these writings were not originally intended by their authors to be regarded as sacred literature comparable to that of the prophets of the Old Testament.

Eventually, Christians did come to think of them this way, but the transition from a collection of writings originally designed to meet certain local problems to the status of sacred Scriptures, either replacing or else being added to the Old Testament, required a comparatively long period of time.

The twenty-seven writings in the New Testament of today were selected from a much larger list, and not until the fourth century was agreement reached among the churches as to the number and selection of writings that should be included (this selection became known as the "canon", from the Greek word meaning "rule"). More about this in our final week.

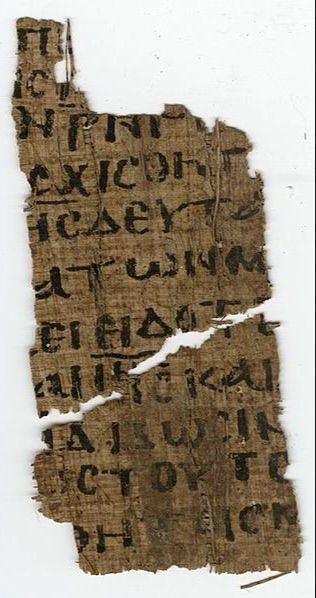

Early papyrus from John's Gospel

Canonicity took the following into account.

- Was the author an apostle/did they have a close connection with an apostle (eg Luke, Paul)?

- Was the work accepted by Jesus Christ (eg the Law and prophets he regularly cited)?

- Was the book accepted by the body of Christ?

- Was it read in churches and quoted in the writings of the early church fathers?

- Did it contain consistency of doctrine?

- Did it agree with overarching rules of faith?

- Did it bear internal evidence of high moral and spiritual values that would reflect a work of the Holy Spirit?

- Did it edify when read publicly and generate a positive heart response

Eyewitness Testimony

Eyewitness testimony is often considered the best evidence of events. The ability of a witness to tell the truth rests in part upon the witness' chronological and geographical nearness to the events. The apostles constantly stressed that they passed both tests:

Luke reports, "This Jesus God raised up again, to which we are all witnesses" (Acts 2:32, NASB).

"what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, and then to the Twelve. After that, he appeared to more than five hundred of the brothers and sisters at the same time, most of whom are still living, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles, and last of all he appeared to me also, as to one abnormally born" (1 Corinthians 15:3-8) (Italics added.)

"For we did not follow cleverly devised tales when we made known to you the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ, but we were eyewitnesses of His majesty" (2 Peter 1:16, NASB).

John wrote, "What was from the beginning, what we have heard, what we have seen with our eyes, what we have looked at and touched with our hands, concerning the Word of Life ... These things we write" (1 John 1:1, 4 NASB).

Since many of the New Testament documents were written within 30 years of the events they record, eyewitnesses would still have been around to correct errors, exaggerations or mistakes.

Early Dating

Not only do the apostles claim to be eyewitnesses, archaeological evidence also supports their chronological and geographical nearness to the events.

A promising means of dating the Gospels early comes from the work of Roman historian, Colin Hemer (1930-1987). He worked backwards from the Book of Acts to the three Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke; more on that later). The Book of Acts is about the origin of the Church, with special focus on the ministries of Peter and Paul. The book includes the martyrdom of Stephen (Acts 7:54-60) and James (Acts 12:1-2), but it says nothing of the deaths of Peter and Paul (between 63-66). Acts also does not include the accounts of the Jewish war with the Romans (66) or the destruction of Jerusalem (in the year 70). Acts ends with Paul's arrest in Rome, without any further discussion about the situation.

These are significant events that (as we have seen) radically altered the relationship between the Romans and Jews. Not including them would be like writing a history of Australia and not including our involvement in the Vietnam War (for argument's sake). If we found such a book, we would rightly conclude that it was most likely written prior to the 1970s. Similarly, since Luke, the writer of Acts, left out such important events as those listed above, it is reasonable to conclude that he wrote Acts before these events took place, around 62 AD. Because Luke was written before Acts, and Matthew and Mark likely before Luke, then the three Synoptic Gospels were written at least before the mid-60s AD. This span is far shorter than the 400 years that elapsed between Alexander the Great's death and his first biography.

In painstaking detail, Hemer combed through each verse of Acts to determine just how careful Luke was as a historian. In the final 16 chapters alone, Hemer identified 84 facts that have recently been substantiated through archaeological and historical research.

There are many other lines of evidence that weigh in favor of the reliability of the New Testament, such as fulfilled prophecy and the testimony of secular sources. The New Testament can be trusted. Remember, our task is not merely to defend the Bible to others, but to absorb its truth so our own lives become the greatest witnesses to Christ.

Manuscript Authority

Can we faithfully reconstruct the original text of the New Testament? Having multiple, early copies gives textual scholars the best chance of success in this endeavour.

The New Testament dwarfs other books of ancient history in this respect. Most ancient books have fewer than 10 existing manuscripts. However, for the New Testament, there are over 5,000 partial or whole Greek manuscripts. If other languages are included, the number jumps beyond 25,000. The eighteenth century brought the recovery of many additional early NT Greek manuscripts which led to great strides in the study of the New Testament text.

Some recent critics, such as Bart Ehrman, author of "Misquoting Jesus," have claimed that there are too many variants across these manuscripts to reconstruct the original with confidence. But this conclusion is too hasty - 80 percent of the variations are simply spelling errors that are easily accounted for. While there is a handful of minor texts upon which some New Testament scholars disagree, there is no textual variation that threatens any central Christian doctrine.

Clement (died 99) extensively quoted Paul's epistles verbatim

Regarding the date between original composition and existing copies, most ancient works have a gap of more than 700 years, with some works, such as Plato and Aristotle, having twice that. In contrast, there are fragments of the Gospel of John dating to within 40 years of composition (John Rylands Papyrus) and a near complete copy of the New Testament within 100-150 years of its original composition (Chester Beatty Papyri).

From a textual point of view, the New Testament documents are exceptional, accurate and reliable documents. And even if all the manuscripts were destroyed, we could reconstruct the entire New Testament (except for 11 verses) through the quotes of the early "church Fathers", who quoted the New Testament (often verbatim) in their writings.

Approaching the New Testament as God's Word

Jesus believed the Old Testament was trustworthy (Matthew 26:54), without error (Luke 16:17) and unbreakable (John 10:35). The authors of the New Testament intended to write reliable history. Or a theologically reliable interpretation of the Gospel in history.

The objective of demonstrating the reliability of the Bible is not to win an argument but to lead people into a relationship with God. The Bible does reveal principles and guidelines for how we should live; but most important, it reveals the person of Jesus Christ. We over-complicate (and gut) the New Testament if we take Jesus out of it; He is central.

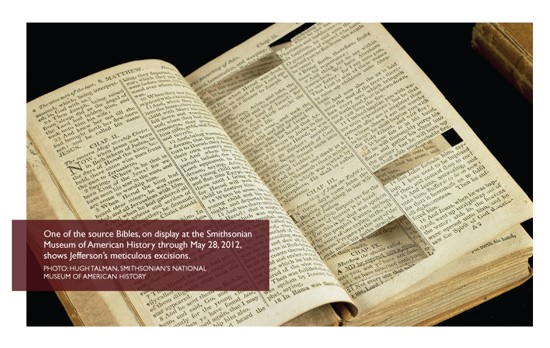

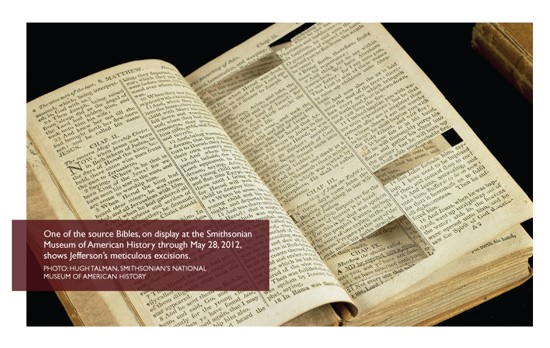

In 1804 US statesman Thomas Jefferson redacted the Bible and produced the Jefferson Bible, or what he called The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, by cutting out and pasting parts that he liked and omitting parts he did not agree with, including the miracles of Jesus and any suggestion that Jesus is God. The virgin birth was gone. So was Jesus walking on water, multiplying the loaves and fishes, and raising Lazarus from the dead. Jefferson's version ends with Jesus' burial on Good Friday. There is no resurrection; no Easter Sunday. Jefferson called the writers of the New Testament "ignorant, unlettered men" who produced "superstitions, fanaticisms, and fabrications". He called the Apostle Paul the "first corrupter of the doctrines of Jesus". He dismissed the concept of the Trinity. He believed that the clergy used religion as a "mere contrivance to filch wealth and power to themselves" and that "in every country and in every age, the priest has been hostile to liberty".

When we take Christ out of the New Testament, we are left with human opinion.

Language and Meaning

The New Testament was written 1,900 years ago, in Greek, in different times. Languages are full of nuances, and there is no way the nuances of the original test can be translated into modern English, Chinese, Quechua or Igbo. A non-Greek speaker would read the text with greater ease than us. A person born a Jew into the NT period would have different understanding to ours. How would an audience of Christians with Gentile backgrounds, who had only a partial understanding of Judaism, have understood what a New Testament Jewish writer was seeking to convey. What weight would they have given (and why) to what they perceived as sacred Jewish writings, especially when the writers quoted the Law, Prophets and writings? How would Jewish audiences have interpreted Gentile quotes and concepts?

What's more, the original text had only upper case letters, no punctuation and no chapter or verse divisions. They were inserted into Greek manuscripts of the New Testament in the 16th century.

- Robert Estienne (Robert Stephanus) was the first to number the verses within each chapter, his verse numbers entering printed editions in 1551 (New Testament) and 1571 (Hebrew Bible).

While first century Antioch was heavily Hellenized, local Christians used Syriac, an Aramaic dialect that served as the literary language of the Christian community in the region. Traders and functionaries would have spoken Greek, the language of commerce, however this was not the case in non-urban areas, where the vernacular obtained. Syriac came to be adopted as the official language of the church in the region. Early Syriac-speaking church fathers subsequently translated the Bible into Syriac. Poets and hierarchs of the early church wrote in Syriac. More than a millennium and a half later, the Syriac language, preserved by the church, continues to be at the heart of Syrian Orthodox identity, unity, discourse, culture, faith liturgy, worship and music. Its deep history and abiding culture remain at the centre of the church's life.

Languages Change

Geneva Bible (1560) |

Tyndale (1549) |

King James Version (1611) |

Passion (2017) |

In 1604, King James I of England authorized that a new translation of the Bible into English be started. It was finished in 1611, just 85 years after the first translation of the New Testament into English appeared (Tyndale, 1526). The Authorized Version, or King James Version, quickly became the standard for English-speaking Protestants. While fewer people read the KJV today, in comparison with other versions (some of which now draw on older manuscripts), its flowing language and prose rhythm has had a profound influence on English language literature during the past 400 years.

Languages change, so it is important that the Word of God be in a version we can understand. Consider the following extract from Canterbury Tales, written in English circa 1387 (if that sounds a long time ago, consider this: the gap between the life of Jesus and Canterbury Tales was twice as long):

He was an esy man to yeve penaunce,

Ther as he wiste to have a good pitaunce.

For unto a povre ordre for to yive

Is signe that a man is wel yshryve;

For if he yaf, he dorste make avaunt,

He wiste that a man was repentaunt;

For many a man so hard is of his herte,

He may nat wepe, althogh hym soore smerte.

Therfore in stede of wepynge and preyeres

Men moote yeve silver to the povre freres

(Prologue, Friar)

Get a version of the Bible that you can understand.

We Need Jesus' World View

We are not islands. We are not neutral. When we look around us, our minds interpret what we see, using hard wiring and coding laid down over a long period. When we open our mouths our world view speaks. When we make decisions, we do so on the basis of our world view priorities. When we process what we see and hear every day, we do so through the filters and architecture of those world views, our ideologies, thought patterns, values and assumptions. What we have devoured we have become. Our beliefs have assumptions embedded in them. What we believe shapes us.

The model for our world view, as Christians, is Jesus Christ. He lived in another age, another culture, which were in many ways alien to our own. His world view was informed by his culture, its belief structures, its nuanced history and its relationship with other nations and cultures. However, it was also instructed by His relationship with Father God.

Jesus was God but He was man; he was man but He was God. He intersected every day with a mix of world communities impacted by sin. He was tempted by community values and pressured by social expectations. But He did not become like His world. As Christians, our minds are to be like His. Without this change in world view, we will never get out of the New Testament what God intends for us.

So, how do we read the New Testament?

The New Testament is made up of 27 "books", written in different styles by different people. Historians and theologians today talk about "hermeneutics", or interpretation.

Almost 2000 years ago, early Christians wrote four accounts of the Gospel (Good News). They contain almost the totality of what we know about the life of Christ. (There are some other "Apocryphal" texts, but these are from later periods and are of unreliable authenticity.) We do not have any of the original manuscripts. However, we do have thousands of copies, made from as early as the first century. The four writers were trying to convey a message about Jesus to their readers. We seek to understand the text through knowledge of its historical origins, eg people, places, things, events, dates, external sources. Many times, the literal sense is easy to discern. Some of the writers knew Jesus personally; others did not. Some were Jews; others were Gentiles.

None of us reads the same way. When we scan a newspaper, we do so with an assumption that it consists of reasonably reliable reporting, but when we turn to the advertisements we have to be much more cautious about the reliability of what is claimed.

- We all know how easily facts can be falsified via social media reporting.

- The UK Government is undertaking an enquiry into "fake news" in the wake of false news scandals circulating around the 2016 Presidential election.

The New Testament consists of a variety of forms: Gospels, letters and Apocalypse. Each form has its own genres, eg parables, miracle stories, sermons, OT quotes and narratives. When we come to the final content we realize that the accounts we have received were selective. The events in Jesus' life were obviously longer than a few weeks, suggested by a straight reading of the Gospels, even if they are put side by side to ensure that we capture everything.

A key question we should ask ourselves is: what did the authors intend to be understood by the recipients? Were the books meant to be read by Jews or Gentiles? What would each audience, eg a church in a locale, have thought about the theology presented? Writers and readers all had different political, economic and social stances and varied experiences and expectations. To what extent were they involved?

The record is not the whole story, but a selection of events. The New Testament does not recount what happened as the first Christians reached out to Africa or Asia (and ended in in far eastern China). What could the writers have possibly intended for us to read, 2000 years later, far removed from the scene of the action, without first-hand knowledge of the culture of the day. This obviously does not limit the meaning of Scripture; the Holy Spirit can apply the words to people with vast different world views.

The writers of the New Testament differed greatly, in background, occupation, age, ethnic group, economic status and education. However, the message is consistent and (we believe) reflects the common inspiration of the Holy Spirit.

How can we get the most out of the New Testament?

We have all heard of Bible Russian roulette, opening the Bible randomly and reading the first words that our eyes fall on, and taking this for "guidance". Perhaps you have heard of the man who found the following "guidance" in quick succession:

- "Then (Judas) went away and hanged himself" (Matthew 27:5)

- "Go and do likewise" (Luke 10:37)

- "What you are about to do, do quickly." (John 13:27)

There is a better way ("inductive"):

- Read the passage.

- Read the surrounding verses, for context

- Read it intentionally.

- Look for the obvious meanings - don't stretch it to include what is not there.

- Consult what others have found (Bible dictionary; commentary; devotionals; Internet, with care).

- Read it for personal application. Try prayer reading.

- Ask the Holy Spirit to help you see any extra meanings He intends for you - this may sound subjective, however all that we truly learn to believe comes to us by revelation; this does not by-pass our logic, but is on another level. Anything additional to the meaning in the text should not violate other Biblical teaching.

- What does the passage say?

- What does the passage mean?

- How does it apply to me?